How to read a museum wall card

All italicized words are from The Met directly.

Image by Peggy and Marco Lachmann-Anke from Pixabay

Let us say that you have not visited a museum in a while, or you have never been. Most museums, regardless of their layout or the exhibits they feature, share a few common characteristics. If you have ever read the sign or label next to a painting or sculpture, you have read something called a museum wall card. So, what is a museum wall card? For starters, you might want to call it a label, but it has also been referred to as a museum plaque.

Here is an image of museum wall cards next to the pop culture powerhouse that is Pokémon. This art exhibit combines museums, the famous art of Van Gogh and Pokémon, in the Van Gogh style. Pokémon like Pikachu is wearing the straw hat of the famous artist. I think it’s great to do this to get people out of the house and into a museum. It gives first time museum visitors something to connect with. It makes the art and museum space very approachable.

At most museums, you will see the traditional version of a wall card. Printed text on heavy card stock. They are also available in digital versions, such as tablets, which allow you to scroll through them. In the case of a painting, it will usually be right next to the work of art. If you are looking at a sculpture, it will be nearby, as they typically do not place them on the pedestal or base that the sculpture sits on. So, check the wall behind the art, or nearby. This can vary from museum to museum and is the curator's choice as to where to place the label.

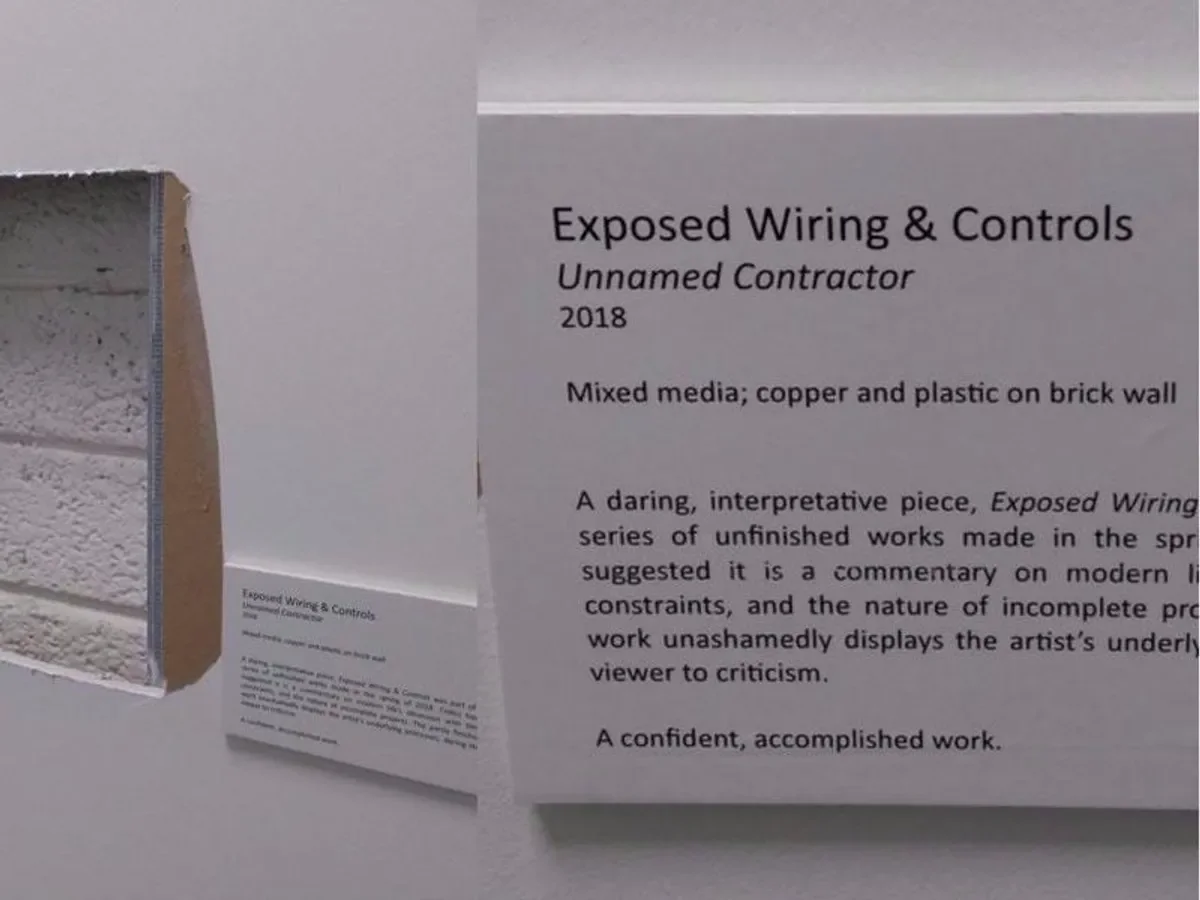

Here is a fun, related image of a wall card created by graphic designer Padraig Murphy. This shows the layout of a museum wall card. It is not for a museum but for an office building. It was made as a fun spoof by the graphic designer. The image comes from https://www.expressandstar.com and was done in light-hearted fun. No one got in trouble for this bit of fun. This is not from a museum, although it is an excellent example of the kind of wall card found in most museums.

Most questions that museum visitors want to have answered can be found on the museum wall card.

Questions such as, "Who is the artist?"

When was it painted?

What is it made of?

What is going on in the scene?

When was something made?

Was this a gift? Is it on loan?

Does the museum own this?

Is it oil paint on canvas?

You might wonder in what year a museum obtained a particular work of art. When did the museum acquire it? Look for the accession or object number. It will be on the very last line of the card. This is a special number that indicates, within a given year, the number of pieces of art the museum has purchased. Included in that number is the year that the painting you are currently looking at, for example, was bought by the museum. I have included a link below that gives examples from the Met in NYC.

Is this work of art on loan? There may also be information on the wall card regarding whether the art is on loan. If the artwork is on loan, it is not owned by the museum and is currently owned by another museum. So, when you see something stating that the artwork is on loan, know that the museum has borrowed it.

Those are some of the most common questions, but they are not the only things the label can cover. Now, with what you are learning in the museum, the wall label answers all your questions, and you’re just ready to move on; that’s fine. You do not have to read every label about every work of art in the museum unless you want to.

Here is an example of a work of art with an unknown artist (These three examples are from museums)

Wall painting fragment—What is it made of?

Roman – Culture that made it, or the location where it was found.

Unknown- we do not know who made it. For older periods, it’s not always known who the artist was.

2nd–3rd century CE - This is around the time it was made. Sometimes, an exact date is not known.

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 171, this information on the museum's website helps visitors locate it in person. The location may or may not be listed. In this case, it is.

Here is the write-up for the fragment:

This charming fragment, depicting a bird surrounded by ivy leaves, is painted with loose, quick brushstrokes unlike the more careful and mannered work of most Pompeian wall paintings. It may have come from a house or, more probably, a tomb, but its origin is unknown.

The Met, Roman, Fresco

Title: Wall painting fragment

Date: 2nd–3rd century CE

Culture: Roman

Medium: Fresco- (A medium is the material used in art to make something.)

Dimensions: 12 1/2 x 11 3/8in. (31.8 x 28.9cm)—Usually, the dimensions are not listed.

Classification: Miscellaneous-Paintings

Credit Line: Gift of Henry G. Marquand, 1892

Object Number: 92.11.10—sometimes called the accession number- mostly for museum purposes.

Museum wall labels are a great starting point to learn more about artwork. That is why I write about topics like this: you do not need to be an art major or know anything about art to jump in and learn. We learn by making mistakes and asking questions. Now, it would be a great starting point to mention that most museums have a library. And if they do not have the book, they can point you in the right direction. I will write about museum libraries soon.

Let us now take a look at another museum wall card, this time by a well-known artist. The American female Impressionist painter Mary Cassatt. The Impressionist style is a popular kind of art that is good for museum beginners.

Here is an example of a work of art done by Mary Cassatt. (Please see link)

In history, we know more about the artist, their work, and the reasons behind their creation. This example originates from the 1800s. By reading the wall card, we understand what is happening in this scene, who painted it, and why. It is much easier in our history to name a male artist than a female one. This is one of the reasons why I picked Mary Cassatt. She is a female impressionist painter, like Van Gogh or Degas. But outside of those who like art, she might not spring to mind. I wanted to use this brief entry to highlight the importance of her being a female impressionist at a time when the field was primarily male-dominated. Not that female artists did not get attention even at the time, but that today most of us can name a male artist.

I will include a link where you can find the image because I do not believe this work is in the public domain. This is just a precaution.

Wikimedia

Here’s what the Metropolitan has to say about the oil painting

Young Mother Sewing

Mary Cassatt

1900

In about 1890 Cassatt redirected her art toward women caring for children and children alone—themes that reflected her affection for her nieces and nephews and the prevailing cultural interest in child rearing. Cassatt enlisted two unrelated models to enact the roles of mother and child for this painting. Louisine Havemeyer, who purchased it in 1901, remarked on its truthfulness: “Look at that little child that has just thrown herself against her mother’s knee, regardless of the result and oblivious to the fact that she could disturb ‘her mamma.’ And she is quite right, she does not disturb her mother. Mamma simply draws back a bit and continues to sew.”

Title

Young Mother Sewing

Artist

Mary Cassatt

Date

1900

Culture

American

Medium

Oil on canvas

Dimensions

36 3/8 x 29 in. (92.4 x 73.7 cm)

Credit Line

H.O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H.O. Havemeyer, 1929

Object No.

29.100.48

View Full Object Record

Signature: [at lower right]: Mary Cassatt

Marking: [stamped on canvas on the back]: F. DUPRE / 144, Faubourg Saint-Honore, 144 / coin de la Rue de Berri, PARIS [also stamped on stretcher; other labels of less significance on the back]

If you would like to see this work of art, you can find it in the following gallery: On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 768.

Please note that there are so many digital versions of the museum wall card online. All you need to do is visit the museum’s website and search for their collection to learn more.

Ask museum staff if you can take a picture of the museum wall card; in most cases, you should be able to. However, each museum has different rules, so if you can't take a photo, grab a pen and paper and take notes, you can even use the back of your paper map. Please note that, as I may have already said, the dimensions are usually not listed on the wall card; it may be listed on the museum website.

Finally, this is the last example of an art wall card with pottery by an American Artist.

Title: Vase

Maker: George E. Ohr (American, Biloxi, Mississippi, 1857–1918, Biloxi, Mississippi)

Date: ca. 1897–1900

Geography: Made in Biloxi, Mississippi, United States

Culture: American

Medium: Earthenware

Dimensions: 6 1/8 x 4 1/2 in. (15.6 x 11.4 cm)

Credit Line: Gift of Robert A. Ellison Jr., 2018

Object Number: 2018.294.174

Vase

George E. Ohr American

ca. 1897–1900

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 707

In many ways, George Edgar Ohr was the quintessential Arts and Crafts potter, combining artistic vision with extraordinary skill with his hands. Working in the seaside resort town of Biloxi, Mississippi, he dug the clay, processed and prepared it, threw the shape on the wheel, altered the piece according to his vision, mixed and applied his own glazes, fired the kiln, created his own style of advertising, and took his wares on the road. Ohr’s personal mantra was "no two alike," and he was as eccentric as his work was individualistic, with its manipulated forms on ultra-thin thrown vessels, crimping, ruffling, off-centering, and twisting, to create unprecedented forms for the 1890s. To these forms, he applied his own completely new and unusual glazes, applied by sponging, splashing, and spattering, resulting in works that in many ways anticipated the abstract art movements that would find form decades later.

Ohr altered his finely thrown pots while they were in a damp, plastic state. This vase features a fairly simple form that has been manipulated in various ways. The walls on bottom half have randomly been pushed in, while the upper half is dominated by a controlled ruffled around the lip. This feature in particular was fairly common on nineteenth-century vessels in many media.

This vase is from the Robert A. Ellison Jr. Collection of American art pottery donated to the Metropolitan Museum in 2017 and 2018. The works in the collection date from the mid-1870s through the 1950s. Together they comprise one of the most comprehensive and important assemblages of this material known. The unparalleled work of George E. Ohr is well represented in the collection. Ellison was an early admirer, collector, and scholar of Ohr’s work and has written extensively on the artist.

The Met, Vase, Ohr, 1900

This wall plaque for pottery, created by the artist Ohr, contains the most detailed information to date. It describes his background, how he created and styled the work of art, and explains his signature at the bottom. I picked this work of art for three reasons. I knew nothing about the artist, and his work in the case was eye-catching. The information on the wall card is incredibly detailed. And finally, I wanted to show that museums do not just have paintings.

When visiting a museum, if something catches your eye, read its wall card to learn more. It might just become your favorite thing of the week. Take down the information on the museum wall card and use it as a starting point to learn more about an artist, a style of artwork, or historical events surrounding the object. The museum wall card is just the beginning of the information that museums can give you. Hopefully, understanding how to read one now and what it entails will help you in the future. I will one day write an article about museum libraries.

Sources:

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/245840

https://www.artic.edu/articles/872/how-to-read-a-label

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/10425

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/20358

Image by Peggy und Marco Lachmann-Anke from Pixabay

Wall Card Image: https://www.expressandstar.com/entertainment/lifestyle/2018/02/28/this-man-stuck-a-museum-label-next-to-a-hole-in-his-office-wall-and-turned-it-into-modern-art/